https://www.gramophone.co.uk/reviews/review?slug=vasco-dantas-poetic-scenes-for-piano

What an interesting and original idea for Vasco Dantas to juxtapose Schumann’s Kinderszenen, Carl Reinecke’s virtually unknown Schumann song transcriptions and piano pieces in the fado tradition. More importantly, the young Portuguese virtuoso is a thoughtful and cultivated musician through and through.

Listen to Dantas’s vocally inspired phrasing in Eduardo Burnay’s Fado, where the melodies fill the room without overwhelming the listener. Likewise, the inherent sentiment of Óscar da Silva’s ‘Fado’ is emotional but not emotive. And Alexandre Rey Colaço’s four Fados couldn’t be more idiomatically and sensitively interpreted. Perhaps Dantas overpoints Vianna da Motta’s ‘Chula’, which flows more naturally in Sofia Lourenço’s recording (Grand Piano). Yet his variegated articulation and faster tempo for ‘Cantiga d’amor’ take pride of place.

Schumann may have been exaggerating when he claimed that Carl Reinecke ‘knows my music by heart before I even composed it’, but I think he meant it. Certainly Reinecke’s song transcriptions are closer to the text and the spirit of the originals than Liszt’s brilliant yet pianistically orientated vantage point. You only need compare both transcribers’ treatment of ‘Widmung’ back-to-back to hear what I mean. Still, Reinecke can be unforgiving to pianists. In ‘Der Nussbaum’, for example, it takes control and discipline to voice the melodic line in the centre of the keyboard with the accompaniment in surrounding registers in order to achieve a convincing ‘three-handed’ effect. Dantas sails through this and similar challenges with no effort.

Fresh ideas abound throughout Kinderszenen. The measured tread and rhetorical tenutos of ‘Hasche-Mann’ depict one who plays blind man’s buff as a strategist rather than a scurrying participant, while alternating dynamics on the down-beats of ‘Bittendes Kind’ impart a different emphasis to each phrase repetition. Dantas begins ‘Wichtige Begebenheit’ with clipped lightness, opening up his tone at the midpoint. He assiduously transitions out of ‘Träumerei’ by easing his way into ‘Am Kamin’ in a questioning, almost tentative manner. No 9’s hobby horse lilts with a firm rhythmic grip, although, like many pianists, Dantas undersells the sudden contrasts in mood of ‘Fürchtenmachen’. ‘Kind im Einschlummern’ is appreciably spacious and introspective but the ritards at phrase ends grow predictable. However, ‘Der Dichter spricht’ provides a lesson in expressive economy, where Dantas reserves the most wiggle-room for left-hand counterlines. Excellent annotations and multichannel sound enhance the appeal of Dantas’s unusual programming and captivating artistry.

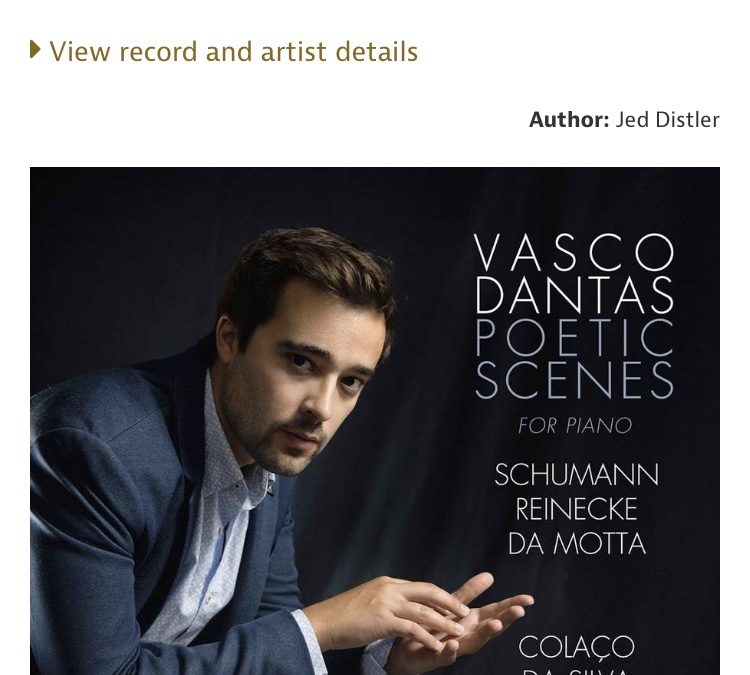

Author: Jed Distler